I was teaching at a boarding school in East Anglia…Suffolk, actually.

It was the worst Christmas ever, and the best in my life.

In the mid-1970s, I was a young man, and arrogant enough to feel anxious when the minicab driver (also, I later learned, a member of the school’s domestic staff) announced “Here we are then.” My anxiety and my ego surged along with my adrenaline when I read a sign that announced “Herringswell Stud Farm.” I can’t tell you my reaction without revealing how full of myself I was. I will say that kidnaping with evil intent was involved.

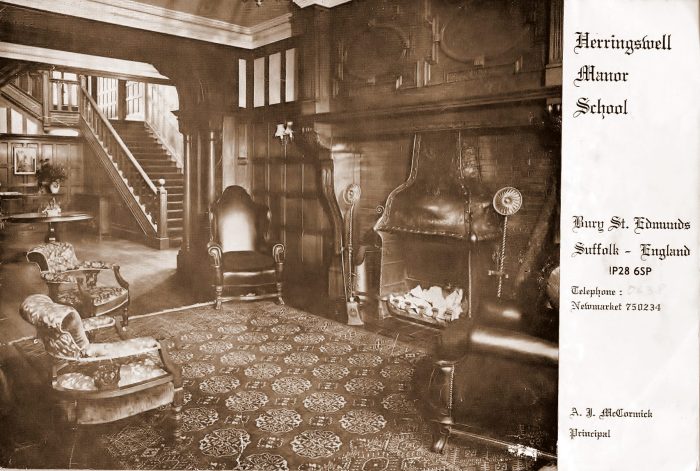

I was much relieved when we turned at the next driveway but one to a different sign, this one announcing “Herringswell Manor School”. As the name might suggest, the school had been established on the site of the original manor house and estate, a mile or so from the village of Herringswell, in horse country, about six miles from Newmarket, known as the birthplace of thoroughbred racing.

Herringswell Manor School was founded mainly through the efforts of Bobo Rockefeller, who wanted a school for her son, Winthrop, later lieutenant governor of Arkansas, whose father had served as governor of that state, and whose uncle had been both vice president of the United States and the governor of New York.

I have wondered whether this location was less than coincidental, as the colonial governors Winthrop of Connecticut and Massachusetts were native to Suffolk, with roots in nearby Lavenham and Edwardstone.

None of that is relevant, but I find it interesting.

So, I was teaching at Herringswell when I experienced the worst Christmas ever, which, in a Dickensian twist, turned out to be the best in my life.

I had enjoyed a wonderful fall holiday on the Norfolk Broads with a group of students whose family did not celebrate Thanksgiving, or who were unable to join their respective families for the holiday.

As naughty and exciting as that might sound, the Norfolk Broads we were plying on a houseboat with a half-dozen boys, comprised the rivers, lakes, and canals around Norfolk. However, it was scenic, relaxing, and more than a little fun.

An abundance of swans populated the waters and our holiday was remarkably free of turmoil and strife, given it was a bunch of boys on a smallish boat for five or six days. I especially enjoyed tying up alongside a pub for dinner and refreshment and investigating the towns and villages along our route.

One of the more interesting events of the week occurred in the busy waterways close in to Norfolk, when we ran aground. I was aft when one of the older boys piloted the boat onto a sandbar. Some of the younger boys immediately began their wonted cries of “Sir, sir!” as they did when anything was amiss.

I checked the time as I made my way forward to the heart of the commotion, amid boys chirping like so many baby birds about running aground and what to do, what to do.

Well, this was not my first rodeo in England, and consulting my watch again, I said, “The first thing we do is have a cup of tea.” I proceeded to suit the action to the word, peppered the meanwhile with earnest enquiries about how to get us unstranded. Crewmen on larger ships passing us in the channel did not let our situation go unspoken and we enjoyed their salty, but good-natured, derision until the tea was done.

The tea was delicious, and with another glance at my wristwatch, I told the student who was piloting to try to back us off again.

A cheer went up as we slid off the sandbar. The boys were amazed at the miracle and all we did was have a cuppa. I told them that that was why it was important to read the tide charts, and we again went merrily on our way.

That, too was irrelevant, but I enjoy the story.

So, now Christmas was coming; the goose was getting fat, and everyone was making plans for getting away from the boarding school for the extended holiday. Students were preparing to go home to Spain or Saudi Arabia or wherever their families found themselves at this time of year, and I arranged for a holiday in Rome.

My nephew, and one of my closest friends, who was stationed in Germany, wrote to say that he could come to England for the holiday. I had not seen him in more than a year and found the prospect exciting, but I wrote back (our residence had no telephone and mobile phones weren’t yet a gleam in the inventor’s eyen.) to say that I had arranged for a holiday in Rome–and, even if I were to stay in England, conditions at the school did not conduce to a festive spirit…or visitors.

Very near the date of departure my travel agent phoned to say that “Rome is overbooked” and I would not be enjoying a very Vatican Christmas.

Well, then Spain, perhaps Ibiza?

No, Spain is booked.

Anywhere! The school would be closed, including the kitchen, and I was eager to be elsewhere.

Sorry, Europe is booked, I was told.

How can an entire continent be booked, I demanded.

“Sir”, said the agent, “No one stays in England over Christmas.”

As it turned out, no one but me.

The school would not offer pleasant accommodations over the holiday. During term the accommodations were Spartan enough, but with no food and no heat excepting an hour or two in the wee hours to keep the pipes from freezing, it did not constitute optimum holiday lodgings.

Instead, another staff member and I decided to take the Cortina to visit Cornwall or Scotland. After much deliberation and planning, we settled on a visit to Cornwall in southwestern England rather than north into the colder Scottish climate.

In preparation for the trip, we had our local mechanic check out the car, which had been exhibiting some signs of imminent ailments. That was the beginning of my relationship with a “slave cylinder,” but I did know about the Civil War (Or as it is known in England, the American Civil War; apparently they had had problems of their own.) and “slave cylinder’ had the ring of certain trouble.

As it happens, our slave cylinder was rebelling. I never had heard of a slave cylinder until our garagiste said that it would not last through a long trip and he could not get to it until after Christmas. We could take a chance on shorter trips, he said, but he strongly advised against trying for Cornwall, or even Scotland, and even shorter trips should be kept to a minimum lest we find ourselves on the side of the road.

Well, here’s another fine kettle of fish.

My colleague shrugged and said that he had friends he could visit, and with that, other than a few domestics coming in to do some cleaning, I had the whole school to myself.

I was less excited than you might think.

The weather turned cold and snow was threatening, so, I walked into Mildenhall, a few miles away, and bought subsistence supplies: cheese, cold cuts, bread, and Haig. Two bottles. I don’t like whiskey, but there it is.

With the heat off for 22-23 hours a day, I found myself dressing in layers and sleeping under a mound of blankets.

I read and watched telly and walked to Mildenhall for…bread. And cheese. Bottle after bottle of cheese, and the odd hot lunch at the small cafe.

I was not jolly. I was not merry, but I did look forward to going to the Bull Inn at Barton Mills of an evening. The roaring fire (It did have a fireplace) not only helped to take the chill off, but the big old fireplace recalled times past as a carriage stop in the long history of the “Olde” inn. I’d enjoy a pint or two with Tommy the barman and sing with the barbershop singers. (Why would you call me a nerd? It isn’t like when I sang with the madrigals at Oxford.

Oh, no, I’ve said too much?)

And every night I’d bundle up for the trudge home and Tommy would say, “Cheerio, sir,” and I’d respond, “Cheerio, Tommy.”

Christmas morning was particularly cold and I was reluctant to get out of bed, but I dragged myself upright and opened the gift my parents had sent. And then…..well, I had gotten in some extra bread and cheese. And Haig. It was a long, cold, dismal day.

Boxing Day was not much better, but the morning after, I was enjoying a pre-prandial or post- breakfast glass of spirits—they did tend to run together—when one of the domestics came by to tell me that I had a phone call in the Lodge.

As we crossed to the Lodge, where our single telephone outside the manor house resided, I found myself perplexed. No one ever called me. With the phone in another building, it was too awkward and time-consuming, even if I were available. When I talked to family, I initiated the call. This was the 70s, after all, and the thought of a mobile was still the stuff of science fiction.

Tentatively, I lifted the handset.

“Hello?”

“Hey, It’s Tom.”

My heart leapt up and without even a rainbow in the sky.

“T,” I exclaimed, “where are you?”

I heard the chuckle in his voice when he said, “Cambridge…at the train station.”

“But I told you that I wasn’t going to be in England over the holiday!”

“I had a feeling.”

I was ecstatic. Just like that, a miserable holiday became a festival of joy.

If that seems overstated, I have not adequately expressed how miserable my holiday had been or how much I loved my nephew. I could not imagine a better surprise, and I promised I’d be in Cambridge as fast as the old Cortina and its cylindrical slave could carry me.

I tend to be a little more demonstrative than T.–or any of my nephews–and when I felt that he was ready to release me long before I was ready to stop hugging him, I didn’t care.

I embarrass easily, particularly in regard to shows of emotion, but this time I didn’t care. I don’t remember any time I was happier to see someone, and he was exceedingly uncomfortable by the time I was ready to let go.

We first went to the Turk’s Head, my favorite restaurant in Cambridge. One floor served steak; another floor served duck; the third floor served steak and duck. The food was delicious and the coffee, served in wine glasses, was dark and rich with an island of cream floating on top. I had so many coffees that Tom tasted one only because he couldn’t believe I would drink so many if they did not contain alcohol.

Over the next few days, we enjoyed many of my favorite places and the Charlie Brownest of Christmases became a time of great joy for me, sharing my favorite places with one of my favorite people.

When a violent storm took out the power, we headed for the Bull Inn, which enjoyed a particularly large crowd. The olde public house was illuminated by candles and warmed by a great roaring fire. It was an evening out of the past, charming, and filled with camaraderie and good fellowship, although, knowing Tom as I do, I declined an invitation to join in the singing. Tom and his sardonic humor would not leave me unscathed should I participate in such a dweebie activity. (He was cool without effort; I was…not.)

All went well and I avoided any activity that might allow him to mock my nerdiness, until we started out the door at the closing bell. Tommy called “Cheerio, sir,” from behind the bar, to which I responded, “Good night, Tommy.”

He stopped drying a glass (Why are barmen continually drying glasses?) and stared. “Cheerio, Sir,” he repeated.

Sigh.

“Cheerio, Tommy,” I responded as usual, and he happily returned to drying a glass.

As we walked away from the pub, I pretended not to notice that Tom was staring at me. When I finally I looked at him, he smirked and said, “Cheerio? Cheerio?” and then snickered like a mad thing.

Well the new term was about to begin and Tom had to return to Germany. I absolutely hated to see him go, but with the boys returning to the residence hall and classes about to resume, I knew that I would soon be absorbed in the regular activities…with heat and food and everything.

But when we got to the train station and Tom boarded his train, there was only one farewell that seemed fitting. As he waved from the top of the steps, I called quietly, “Cheerio, T,” and he exited laughing, leaving me with wonderful memories of the best Christmas ever.

And now, I wish you a very happy Christmas, and–for now–Cheerio.